Religion, Creationism, evolution, science and politics from a centre-left atheist humanist. The blog religious frauds tell lies about.

Showing posts with label Ecology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Ecology. Show all posts

Thursday 18 April 2024

How Science Works - Darwin's Wonderful Worms Revisited

How a little-known clergyman studying worms by candlelight in the 1700s inspired Charles Darwin – but didn’t get the credit he deserved

Almost exactly 10 years ago today, I wrote an article in praise of the last work Charles Darwin wrote about, in 1881, where he showed how earthworms were not the garden pests they had been assumed to be, but how they were essential for creating the soil and how their activity had transformed the landscape. He showed how they were responsible for burying very much of history, transforming the budding science of archaeology.

He also showed how the planet is not a static place, unchanged since its 'creation' like the Christian dogma taught, but a dynamic and changing place where the present has been shaped by natural forces which were also responsible for the history that archaeology and geology were revealing.

So, it's rewarding to write about how Darwin did this research and particularly how he built on the knowledge of those who had gone before him, in the best traditions of science, where knowledge is accumulative and build on the known to discover the unknown and so advance the sum total of human knowledge. The sad thing is that either deliberately, or through forgetfulness in his advanced years, Darwin neglected to give due credit to Rev. Gilbert White.

This is the subject of an article by Kevin Richard Butt, a Reader in Ecology, University of Central Lancashire, UK, published in The Conversation. His article is reprinted under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency:

Labels:

Bigotry

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Nature

Saturday 27 January 2024

Creationism in Crisis - Evolution In Progress As a Tiny Ant Changes The Ecosystem.

Tiny ant species disrupts lion’s hunting behavior - News - University of Florida

As well as species evolving, there is another form of biological evolution that is often not recognised as such - the evolution of ecosystems as the populations of species that exist within it changes.

Environmental change is the prerequisite of evolutionary change on the classic Darwinian evolution by natural selection model, so we would expect to see an evolutionary change to significant environmental change, given time, but changes to delicately-balanced ecosystems can occur very quickly - in a matter of years or even months, whereas evolutionary change in the species gene pool will normally take many generations to occur, and that slow response to ecosystem change often results in extinction or sometimes, in favourable conditions, a population boom.

And one such ecosystem change is currently underway in Africa due to a small, invasive species of ant, as Professor Todd Palmer, an ecologist and professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Florida, with colleagues including University of Wyoming doctoral candidate and Kenyan scientist Douglas Kamaru, Jake Goheen, from the University of Wyoming, and Corinna Riginos, with The Nature Conservancy reported recently in Science.

I have remarked several times elsewhere how, because the giraffe's long neck and legs have evolved in an arms race with acacia trees, if acacia trees disappeared what is now an advantage to giraffes, would become a handicap as they find drinking difficult and are vulnerable to predation by lions and leopards as they drink because they can't raise their heads up rapidly without a dangerous fall in blood pressure to their brain and that, together their spread-eagled legs, mean they can't suddenly get up and run. Their long necks and legs only make sense in the presence of acacia trees.

And acacia trees have also been evolving in this expensive -do-or-die arms race with giraffes and other browsing species, in which the massive cost of producing enough sugar to build such a tall trunk would also be a handicap in the absence of giraffes. But, in one of those serendipitous turns of good fortune, acacia trees have an ally in this arms race in the form of vicious ants of the Pseudomyrmex and Crematogaster genera that take up residence in swellings at the base of thorns in the crown of the tree. These ants vigorously defend the trees against not only giraffes, but also elephants which can reach to lower branches with their trunks and will even push them over to get at the leaves.

The close interdependence of acacia trees and these ants is an example of co-evolved mutualism:

Labels:

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Geochronology

,

Palaeontology

,

Parasites

,

Science

Monday 22 January 2024

How Science Works - Correcting A Mistake About Megalodons - But Still Biting A Chunk Out Of Creationism

The Megalodon was less mega than previously believed | News

A scientific principle that creationists seem to find baffling, is based on the intellectually honest position that opinion must be guided by evidence. It is that scientific opinion is always provisional and subject to change if the evidence changes, so evidence is frequently re-examined and reassesses, and scientific opinion is adjusted accordingly. This is why science textbooks are revised periodically and new editions produced, incorporating the newer thinking,

A simple analogy is that of driving to an airport to catch an important flight. You might check the expected driving time by checking in an old route planner from the 1950's, which might tell you the journey, in the days before traffic congestion, would take about 90 minutes, then you might check a few days before the flight, using an online route planner and learn that the journey will take about 2 hours at that time of day.

Do you just regard the 1950's version as an indisputable fact and plan your journey accordingly? How about the one a few days ago? No! A sensible person, regards both those as provisional pending more up-to-date information, and checks again on the day, when they might discover that there is a road closure and a diversion in place, or there is a serious incident on the motorway, reducing the traffic to a slow crawl for 20 miles, so the journey will now take 3 hours. Was the first estimate wrong? Which is the best estimate to go with now? The old ones based on information available at that time, which might have caused you to miss your flight, or the new one based on updated information?

On that analogy, creationists are in the position of using information not from the 1950s, but from the Bronze Age, some of it from a time before even the wheel was invented, let alone air-transport, motor cars or motorways!

In 2022, based on very scant information (a tooth and some vertebrae), a team of researchers estimated the size of an extinct shark, the megalodon (big tooth) shark, Otodus megalodon, to be at least 50 feet long, and possibly as much as 65 feet. This was based in the assumption that O. megalodon was like a scaled up great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, so its dimensions could be estimated by comparing what they had with those of C. carcharias.

Now a team or researchers co-led by biologist, Phillip Sternes of the University of California Riverside (UCR), and DePaul University paleobiology, Professor Kenshu Shimada, have reassessed the evidence and concludes that O. megalodon was slimmer than the great white but probably considerably longer than the earlier estimate. This greater length would probably have meant a more efficient digestive system having longer to digest food and extract nutrients from it, so its hunting and predation would have had less impact on the ecosystem than first thought. It would still have been an apex predator but maybe not as voracious as first thought.

Their research is published in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica, an explained in a UCR news release:

Labels:

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Palaeontology

,

Science

Wednesday 17 January 2024

Creationism in Crisis - Scientist Got A Date Wrong - But It's More Bad News For Creationists

A Pacific harbor seal swims through a kelp forest in Monterey Bay, California. Recently discovered fossils from Washington show that kelp forests flourished more than 32 million years ago along the Pacific Coast, long before seals and other animals appeared.

Pacific kelp forests are far older than we thought | Berkeley

It used to be thought that the ecosystems along California's coasts, which are centred on kelp forests, evolved about 14 million years ago but the discovery of 32-million-year-old fossil kelp means that estimate needs to be revised to a time before the modern marine mammals, urchins, birds and molluscs which now depend on these ecosystems had evolved.

It also means that kelp was probably an important food for a now-extinct hippopotamus-sized marine mammals, the desmostylians, probable relatives of manatees, sea cows and their terrestrial relatives, elephants.

The 14-million-year-old estimate assumed that all components of an ecosystem co-evolve, but this finding shows that the same foundation can lead to different ecosystems to evolve around them, consistent with new niches providing evolutionary opportunities in which mutation and variance can be selected for. In other words, the meaning of the genetic information is changed by the environment.

The discovery of the fossil kelp holdfasts and its significance is explained in a published paper In Proceeding of the National Academy of Science (PNAS) and in a news release from the University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley):

Labels:

Biology

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Science

Thursday 11 January 2024

Creationism in Crisis - How Mindless Evolution Took A Giant Ape To Extinction

A reconstruction of Gigantopithecus blacki.

Image: Garcia / Joannes-Boyau

The Extinction of the Giant Ape--A Long-standing Mystery Solved--Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

Limestone karst landscape in Chongzuo, southern China. The Gigantopithecus sites are located in caves in the steep-sided walls of the mountains. The mountain in the center of the picture is Mulan Mountain. The entrance of Hejiang Cave (#16 in Figure 2) is about three-quarters down from the main peak.

The reason for its extinction remained a mystery until now, when a team of researchers from Chinese, Australian and American universities have shown that extinction was almost certainly caused by climate change which deprived it of its highly specialised food - tree bark.

The story of its evolution and eventual extinction illustrates the unplanned and mindless nature of evolution by Natural Selection which has no mechanism for anticipating, let alone planning for a major event like climate change causing forest to become grasslands. There is no Plan B because there is not even a Plan A. The large size of Gigantopithecus was probably related to its diet of tree bark, which can be deduced from its teeth and jaw. A large gut being needed to digest, with the aid of bacteria and other microorganisms, a high-cellulose diet. And a large body needs a lot of food to sustain it. Compare the size of the wholly vegetarian gorilla with that of the more omnivorous chimpanzees.

The researchers have published their findings, open access, in the journal Nature and explain it in a news release from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences:

Labels:

Climate

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Science

,

Unintelligent Design

Sunday 26 November 2023

Unintelligent Design - Why Skunks Have Evolved Different Colour Patterns

Four skunks, four different patterns

November: Skunks' warning stripes | News and features | University of Bristol

It's better to warn than to attack because attacking is costly and carries risks, but a warning is often free or takes minimal effort.

This is why many creatures advertise the fact that they can be dangerous so leave them alone - yellow and black wasps; the warning rattle of a rattlesnake, the bright colours of a poison dart frog, or the black and white pattern of a skunk, for example.

But these patterns only work as a deterrent, if the potential threat has some experience or has evolved in their presence so has a genetic aversion.

Labels:

Arms Races

,

Biology

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Science

,

Unintelligent Design

Wednesday 15 November 2023

Creationism in Crisis - The Diverse Landscape Of 'Pre-Creation' Europe

Illustrations by Brennan Stokkerman

Fig. 4.

Palaeoartistic reconstructions of Last Interglacial landscapes in the European temperate forest biome, consistent with our pollen-based estimates of vegetation structure.

Typical Last Interglacial fauna are shown, such as the extinct straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), an extinct rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis), and aurochs (Bos primigenius, the extinct wild form of contemporary domestic and feral cattle), alongside common extant species: fallow deer (Dama dama), a great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major), a European robin (Erithacus rubecula), and greylag geese (Anser anser). (Top left) Early-temperate period: Light woodland, including a mix of taller trees and the shrub hazel (Corylus avellana), and grass-dominated open vegetation. (Top right) Early-temperate period: Open, grassy vegetation interspersed with light woodland and bordering closed forest with shade-tolerant trees. (Bottom left) Late-temperate period: Light woodland, denser forest with frequent hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), and some open vegetation (front). (Bottom right) Late-temperate period: Open grass- and sedge-dominated vegetation with free-standing deciduous oaks (Quercus robur), with more closed tree stands in the background.

Palaeoartistic reconstructions of Last Interglacial landscapes in the European temperate forest biome, consistent with our pollen-based estimates of vegetation structure.

Typical Last Interglacial fauna are shown, such as the extinct straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), an extinct rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis), and aurochs (Bos primigenius, the extinct wild form of contemporary domestic and feral cattle), alongside common extant species: fallow deer (Dama dama), a great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major), a European robin (Erithacus rubecula), and greylag geese (Anser anser). (Top left) Early-temperate period: Light woodland, including a mix of taller trees and the shrub hazel (Corylus avellana), and grass-dominated open vegetation. (Top right) Early-temperate period: Open, grassy vegetation interspersed with light woodland and bordering closed forest with shade-tolerant trees. (Bottom left) Late-temperate period: Light woodland, denser forest with frequent hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), and some open vegetation (front). (Bottom right) Late-temperate period: Open grass- and sedge-dominated vegetation with free-standing deciduous oaks (Quercus robur), with more closed tree stands in the background.

Illustrator: Brennan Stokkermans.

Pearce, E. A.; Mazier, F.; Normand, S., et al. (2023) (CC BY 4.0)

Pearce, E. A.; Mazier, F.; Normand, S., et al. (2023) (CC BY 4.0)

Researchers led by Elena A. Pearce of the Department of Biology, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark, have looked again at the evidence for the flora and fauna of Europe during the last interglacial period (130,000 -150,000 years ago) and believe they have shown that the previous assumption that Europe was covered in dense woodland prior to the arrival of modern human, may be wrong. Europe was, instead, "full of variation. Importantly, the landscapes harboured large amounts of open and semi-open vegetation with shrubs, light-demanding trees and herbs alongside stands of tall-growing shade trees."

When was the last interglacial period in Europe and what caused it? The last interglacial period in Europe occurred during the Pleistocene epoch, specifically the Eemian interglacial. The Eemian interglacial is estimated to have occurred roughly between 130,000 and 115,000 years ago. It was a relatively warm period when temperatures were higher than during the subsequent Last Glacial Maximum.The team arrived at their conclusion after examining pollen grains from soil samples taken from large parts of Europe.

The primary cause of glacial-interglacial cycles, including the Eemian interglacial, is believed to be variations in Earth's orbit and axial tilt, collectively known as Milankovitch cycles. These variations influence the amount and distribution of solar radiation reaching the Earth's surface. The interplay of these orbital parameters results in periodic changes in climate, leading to alternating glacial and interglacial periods.

During interglacial periods, such as the Eemian, temperatures were warmer, and ice sheets and glaciers retreated. This warmer climate allowed for the expansion of forests and the development of different ecosystems compared to the colder glacial periods. It's important to note that natural climate variability, driven by factors like Milankovitch cycles, played a significant role in past climate changes, but contemporary climate change is also influenced by human activities, particularly the emission of greenhouse gases.

Labels:

Climate

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Geology

,

Palaeontology

,

Science

Wednesday 25 October 2023

Creationism in Crisis - Research Shows How Environment Drives Evolution - No Magic Required

Raining Cats and Dogs: Research Finds Global Precipitation Patterns a Driver for Animal Diversity

A team of researcher from Utah University's Department of Watershed Sciences in Quinney College of Natural Resources and the Ecology Center, led by Jaron Adkins, has investigated why there is a rich diversity of species in some areas and a paucity of species in others. Not surprisingly, given what we know of how diversity evolves due to environmental selectors, they found a close link between diversity and the environment, especially rainfall, and the result of rainfall, or a lack of it - plant growth.

Labels:

Biodiversity

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Environment

,

Evolution

,

Science

Sunday 3 September 2023

Unintelligent Design - The Ludicrous Complexity, High Risk and Prolific Waste in Bamboo Reproduction

Bamboo, Phyllostachys nigra var. henonis, flowering

Toshihiro Yamada

Hiroshima University

Hiroshima University

Flowering for naught: 120 years with nothing to show | Hiroshima University

If you want an example of something that no even half competent, intelligent designer would come up with, but exactly the sort of thing a mindless, undirected, utilitarian process such as evolution by natural selection, can produce, you need look no further than bamboo.

Bamboo is monocarpic, i.e., like many annual and biennial plants it flowers once, then dies. However, unlike most monocarpic plants that take just one of two, maybe a few years, to flower, bamboo of the variety hedonis takes 120 years.

To make matters worse, because they all germinated at the same time after the last flowering, all the bamboo plants in the local area flower and die at the same time, devastating an ecosystem that had been forming for 120 years, as food crop, and even providing raw materials for local crafts. And then it's gone, reverting to grassland for the three or more years it takes for the new generation to reestablish itself.

As though that weren't bad enough, researchers at Hiroshima University have now shown that there is a very low success rate in germinating seeds as most of them are sterile and fail to germinate.

The last time this variety of bamboo flowered was in 1908, so, in a few years, there is a very real risk that var. hedonis could become extinct.

The problem is explained in a Hiroshima University News release:

Labels:

Biology

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Science

,

Unintelligent Design

Saturday 19 August 2023

Creationism in Crisis - A Mass Extinction in Southern California, 7000 Years Before Creationists Think Earth Was Created!

A mural in the Page Museum depicts hundreds of species whose fossils have been found in the La Brea Tar Pits.

Credit: Mark Hallett.

Illustration depicting the hunting behavior of La Brea carnivores, including saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and coyotes.

Credit: Mauricio Antón

It’s hardly surprising anymore because all but the most recent history of Earth took place millions, even billions of years before Earth was created, according to Creationists’ literal reading of the Bronze Age creation myth recorded in the Bible, but here we have evidence of a sudden mass extinction in Southern California, not by a genocidal global flood, but by rapid climate change, human activity and devastating regional fires.

This is the conclusion of a detailed study by a team of scientists that included Texas A&M University archaeologist, Dr. Michael Waters. The team focused on the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits.

First a little AI information about the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits:

The Rancho La Brea Tar PitsThe work of the scientists is explained in a news release from Texas A&M:

The Rancho La Brea Tar Pits, also known as the La Brea Tar Pits, is a famous fossil excavation site located in the Miracle Mile district of Los Angeles, California, USA. It is one of the most significant paleontological sites in the world and has provided an incredible wealth of information about the prehistoric life that existed in the region during the Pleistocene epoch. Here are some key points about the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits:The Rancho La Brea Tar Pits are a unique and invaluable resource for understanding the ancient history of Southern California and the diverse range of life that once inhabited the region. The site's ongoing excavations and research contribute to our understanding of prehistoric ecosystems and the interactions between humans and the environment during that time.

- Formation: The tar pits were formed as a result of crude oil seeping to the surface from underground deposits. The oil would bubble up to the surface, forming pools of sticky asphalt or tar. These pools were often covered by water, leaves, and other debris, which attracted animals that became trapped in the tar.

- Fossil Preservation: The unique conditions of the tar pits resulted in excellent preservation of the trapped animals. The tar's stickiness trapped animals, and the lack of oxygen and bacteria in the tar slowed down decomposition. Over time, bones and other remains of animals accumulated in the pits.

- Prehistoric Fauna: The tar pits contain a wide variety of fossils, including those of mammals, birds, reptiles, and plants. Some of the most common animals found in the pits include dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, and various species of birds.

- Research and Discoveries: Excavations at the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits began in the early 20th century. The first scientific excavations took place in the early 1900s, and since then, thousands of fossils have been recovered. These fossils have provided invaluable insights into the animals that lived in the Los Angeles area during the Pleistocene epoch, which occurred approximately 10,000 to 40,000 years ago.

- Page Museum: The George C. Page Museum, now known as the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum, was established in 1977 near the tar pits. It houses a vast collection of fossils and artifacts recovered from the site. The museum also includes exhibits that provide information about the history of the tar pits, the animals that were trapped there, and the science of paleontology.

- Active Excavations: Despite decades of research and excavation, the tar pits are still actively studied and excavated. New discoveries continue to shed light on the ancient ecosystem of the region.

- Public Engagement: The La Brea Tar Pits and Museum offers educational programs, guided tours, and interactive exhibits for visitors of all ages. It's a popular destination for tourists, students, and researchers interested in paleontology and natural history.

ChatGPT3.5 "Tell me all about the Rancho La Brea tarpit" [Response to user request]

Retrieved from https://chat.openai.com/

Wednesday 31 May 2023

Creationism in Crisis - Australia's Dingos are Still Distinct and Showing Signs of Speciation

Slideshow code developed in collaboration with ChatGPT3 at https://chat.openai.com/

New DNA testing shatters 'wild dog' myth: most dingoes are pure

Recent new findings illustrate the way a species will evolve by diverging into related species that may still be able to interbreed even though other indicators show that they should be regarded as a distinct species. It also shows how a single species can diverge into populations as the precursor to evolving into subspecies and then species.

How are dingoes unique?It also shows how, as science refines and improves its techniques, new information brings about a change of consensus in a classic example of scientific opinion changing when the information changes, unlike religion which needs to find reasons not to change its collective mind despite new information, or risk another fragmentation into mutually hostile sects.

Dingoes possess several unique characteristics that distinguish them from domestic dogs and wolves. These characteristics include:It's important to note that while these characteristics are typical of dingoes, there can be variations among individuals and populations. Additionally, some of these traits may be influenced by interbreeding between dingoes and domestic dogs, which can introduce genetic diversity into the dingo population.

- Size and Body Proportions: Dingoes are typically smaller than wolves and many domestic dog breeds. They exhibit a lean and agile body structure with a head that is broader and flatter than that of domestic dogs.

- Coat Color and Texture: Dingoes commonly have a sandy or reddish-brown coat color, although variations can occur. Their coat is usually short, dense, and well-adapted to the Australian climate. Some dingoes have a white chest and facial markings.

- Cranial Features: Dingoes often have a skull shape that is different from both domestic dogs and wolves. Their skull is generally longer and less domed than that of most dogs, with a narrower zygomatic arch (cheekbone) region.

- Dentition: Dingoes possess a unique set of teeth, including relatively large canine teeth and sharp carnassial teeth adapted for cutting flesh. Compared to domestic dogs, their teeth are generally larger and exhibit less size variation.

- Behavior and Social Structure: Dingoes are highly adaptable and display behavior suited to their semi-arid and arid habitats. They are generally more independent and less social than domestic dogs. Dingoes often live in small packs or as solitary individuals, whereas wolves form larger, more structured packs.

- Reproduction and Breeding: Dingoes typically have a different breeding cycle than domestic dogs, with a once-a-year breeding season. They also exhibit different mating behaviors and have fewer puppies per litter compared to many domestic dog breeds.

ChatGPT3 "What are the unique characteristics that distinguish dingoes from domestic dogs and wolves?" [Response to user question]

Retrieved from https://chat.openai.com/

The study is a re-examination and re-evaluation of the status of the Australian dingo, Canis dingo, in view of improved DNA testing. Using earlier techniques which involved comparing just 23 DNA markers, geneticists had concluded that there were very few pure-bred dingoes left as most had DNA derived from hybridization with feral domestic dogs, Canis familiaris. On that basis, the dingo was reclassified as a wild dog and an invasive pest, and several eradication programs were implemented.

But a new study, using newer techniques which enable the scientists to compare not just 23 but 195,000 DNA markers has revealed a very different picture. This shows not only that ingression of familiaris DNA has been very limited in some areas, but that the dingo species can be regarded as four distinct populations. In other words, not only is the dingo still a species distinct from feral dogs but the dingo species is showing early signs of speciating.

It is now accepted that dingoes have not evolved directly from wolves so are not a subspecies of Canis lupus but are descended from the Southeast Asian domestic dog, meaning they were taken to Australia by humans and have evolved to adapt to the Australian environment. They have also been there so long that they have become an important part of the Australian ecosystem as apex predators, so can't now be regarded as an alien species, unlike rabbits, rats, European foxes, mice, cane toads and domestic cats.

The new study, by geneticists from the University of New South Wales and Sydney University, NSW, Australia, with colleagues in the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, is published, open access, in the journal Molecular Ecology.

Three of the scientists, Kylie M Cairns, Research fellow, UNSW Sydney, Mathew Crowther, Associate professor, University of Sydney and Professor Mike Letnic, Evolution and Ecology Research Centre, UNSW Sydney have explained their research and its significance for dingo conservation in an article in The Conversation. Their article is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency.

Wednesday 15 March 2023

Climate Emergency News - Large-Scale Failure of Entire Bird Population to Breed

Climate Emergency News

Large-Scale Failure of Entire Bird Population to Breed

Large-Scale Failure of Entire Bird Population to Breed

Dronning Maud Land (Queen Maud Land), Antarctica

Extreme snowstorms lead to large-scale seabird breeding failures in Antarctica: Current Biology

According to a survey published, open access, yesterday in the Cell Press journal, Current Biology almost the entire breeding population of three seabirds failed to breed on important breeding grounds in Antarctica, due to unseasonably high snowfall in the Antarctic 'Summer' (December 2020-January 2022) when breeding normally takes place. The unusual weather is almost certainly due to man-made climate change.

The researchers found not a single nest of the South Polar skua, and only a handful of the nests of the Antarctic petrel, Thalassoica antarctica, and Snow petrel, Pagodroma nivea, on the main breeding ground of Dronning Maud Land (Queen Maud Land) in the Norwegian-administered sector of Antarctica.

According to information from Cell Press:

Sunday 11 December 2022

Ecology News - How Photos From Space Have Changed Our View of Earth And Our Place In The Cosmos

Looking back from beyond the Moon: how views from space have changed the way we see Earth

In the words of the late, great Carl Sagan, looking at a picture of a tiny image of Earth seen through one of the rings of Saturn:

In the words of the late, great Carl Sagan, looking at a picture of a tiny image of Earth seen through one of the rings of Saturn:

In the following article reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, Professor Alice Gorman, Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University, Australia, looks at the way images of Earth taken from space, have influenced our thinking about Earth and our place in the Cosmos.

The article is reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here:

Earth is a bright pixel when photographed from "Voyager 1" six billion kilometres out (past Pluto).

NASA

Updated by Kevin M. Gill using modern image-processing techniques, 2020

Updated by Kevin M. Gill using modern image-processing techniques, 2020

Consider again that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it, everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever lived, lived out their lives. The aggregate of all our joys and sufferings, thousands of confident religions, ideologies and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilizations, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, every hopeful child, every inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species, lived there on a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam.The ludicrous Creationist claim that the Universe is somehow 'fine-tuned' for life is given the lie by the simple realisation that, a short distance from the surface of our planet, life becomes completely untenable in a very hostile environment. Life is 'fine-tuned for Earth because the process of evolution, by which living things became the way they are, is the tuning process.

The earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and in triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner of the dot. How frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light.

Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity — in all this vastness — there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves…… It is up to us. It’s been said that astronomy is a humbling, a character-building experience. To my mind, there is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another and to preserve and cherish that pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.

In the following article reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license, Professor Alice Gorman, Associate Professor in Archaeology and Space Studies, Flinders University, Australia, looks at the way images of Earth taken from space, have influenced our thinking about Earth and our place in the Cosmos.

The article is reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here:

Saturday 26 November 2022

Creationism in Crisis - Fossils from Gondwana Show Evolution and Ecosystems 266 Million Years Ago

Exquisite new fossils from South Africa offer a glimpse into a thriving ecosystem 266 million years ago

Creationist frauds who want to convince their cult members that the Theory of Evolution is about to be replaced in mainstream science by their childish superstition, and so become the first scientific theory ever to be replaced with an evidence-free superstition involving imaginary supernatural entities, have to keep them ignorant of papers such as this one which has just been published in Communications Biology.

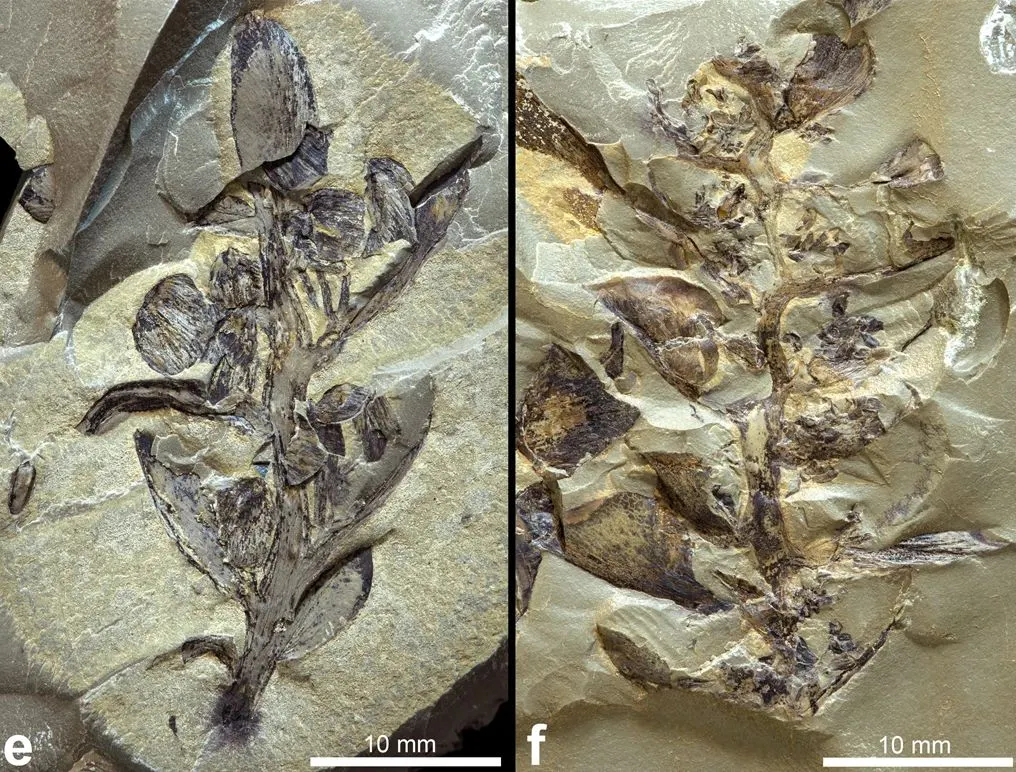

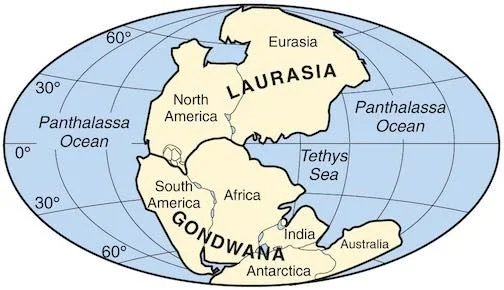

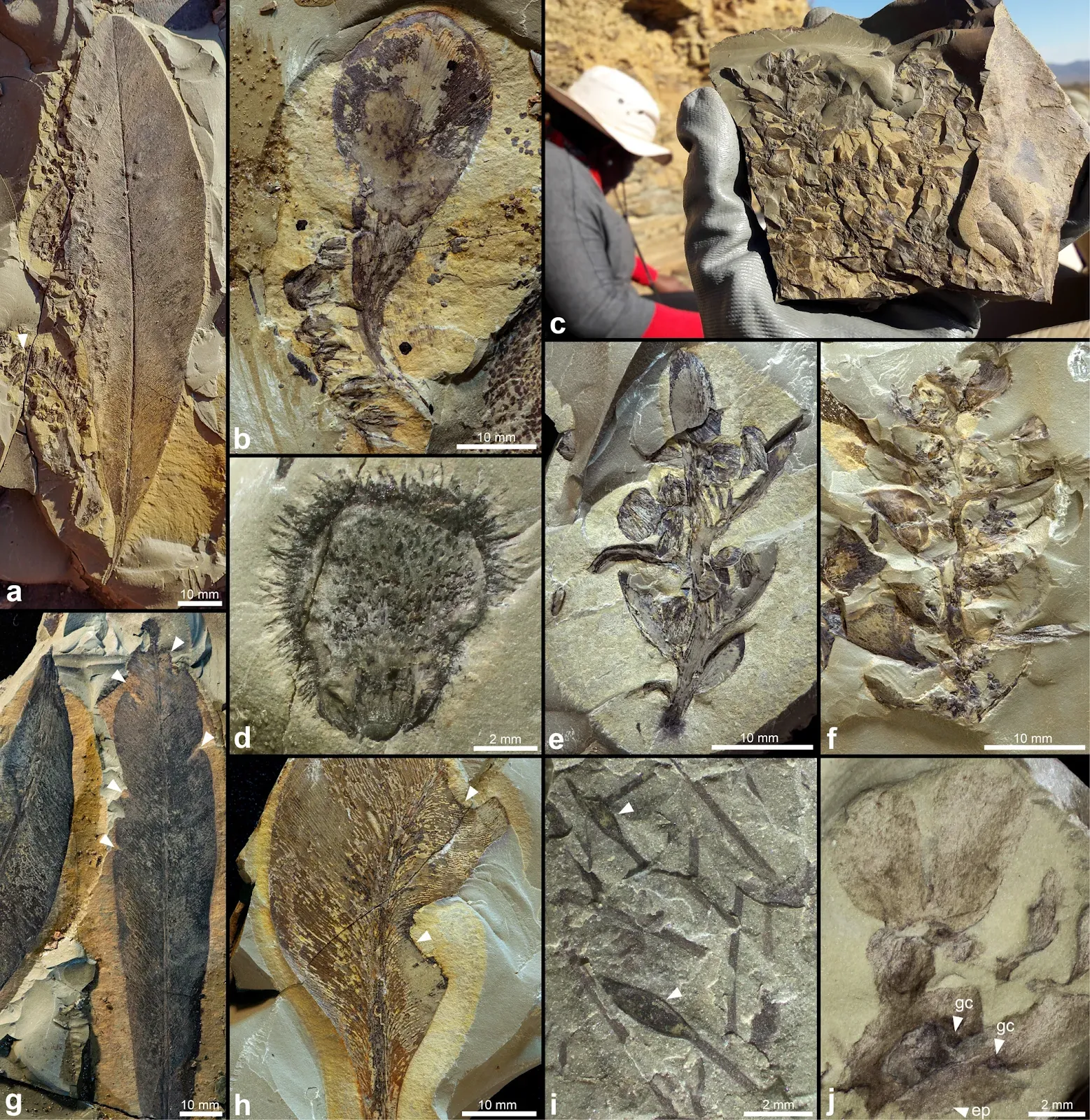

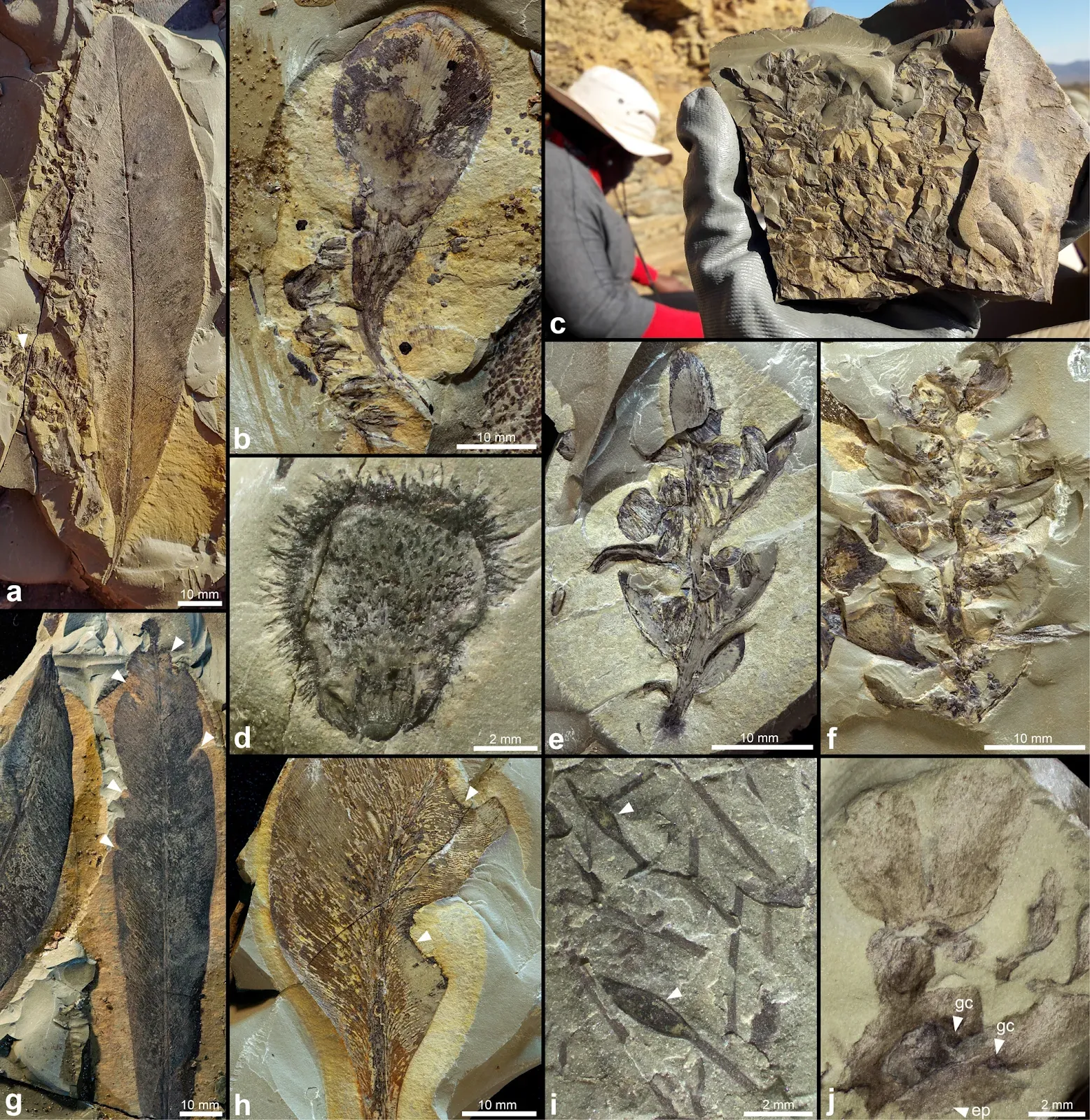

The paper, by a team of scientists led by Rosemary Prevec, a palaeontologist with Rhodes University Department of Botany, and the Department of Earth Science, Albany Museum, Makhanda, South Africa, reports on an exceptionally well preserved collection of fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids and plants - what is known to science as a 'Lagerstätte'. What's more, the formation has 'robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context', in other words, the fossils can be accurately placed in time and the changing geography of the time - some 266–268 million years ago in a river delta, when Earth had just two major landmass known as Gondwana and Laurasia, the northern and southern parts of Pangea respectively, before they were broken up and in some cases forced together by tectonic forces to form today’s major continents.

These fossils enabled the team to reconstruct the ecosystem of the time. An ecosystem is the result of interactions between species of animals and plants in a given area - the fundamental conditions for evolution to occur, as the ecosystem changes in response to internal and external pressures.

The team leader, Rosemary Prevec, has written the following article in The Conversation to explain the background to the discovery and its significance in terms of understanding the evolution of some species and the extinction of others. The Theory of Evolution is, of course, fundamental to research such as this in order to make sense of the observations. Note that nowhere does the author show the slightest doubt about the TOE's value in that understanding.

Her article is reproduced under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Rosemary Prevec, Rhodes University

South Africa is famous for its amazingly rich and diverse fossil record. The country’s rocks document more than 3.5 billion years of life on Earth: ancient forms of bacterial life, the emergence of life onto land, the evolution of seed-producing plants, reptiles, dinosaurs and mammals – and humanity.

Many will be familiar with hominid fossils such as the Australopithecus africanus skull Mrs (or is it Mr?) Ples and the paradigm-shifting Taung child. Less well known and equally important fossils such as the oldest terrestrial vertebrates in the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which document the first steps from the ocean and onto land, have also emerged from South Africa. The country’s wealth of fossils is due in part to the region’s unique geology, which documents 100 million years of nearly continuous deposition in its Karoo Basin.

Fossils also hold clues to climatic shifts, from the great Carboniferous ice age over 300 million years ago, to the huge dunes of blazing Jurassic deserts where dinosaurs roamed 200 million years ago. Scientists can read the devastation of the mass extinction events that destroyed global ecosystems and changed the course of Earth’s history.

But in the race to understand the “big picture” of the evolution of life and to distil its dramatic ups and downs into punchy headlines, it is easy to forget the small and quiet things. Pause, and consider what life looked like on an average day, in a world without humans, mammals, birds, butterflies, flowers, or even dinosaurs. What was it like on the shores of a rippling lake, on a drowsy summer afternoon, 266 million years ago in what’s now the Northern Cape province of South Africa?

The search, and what we found

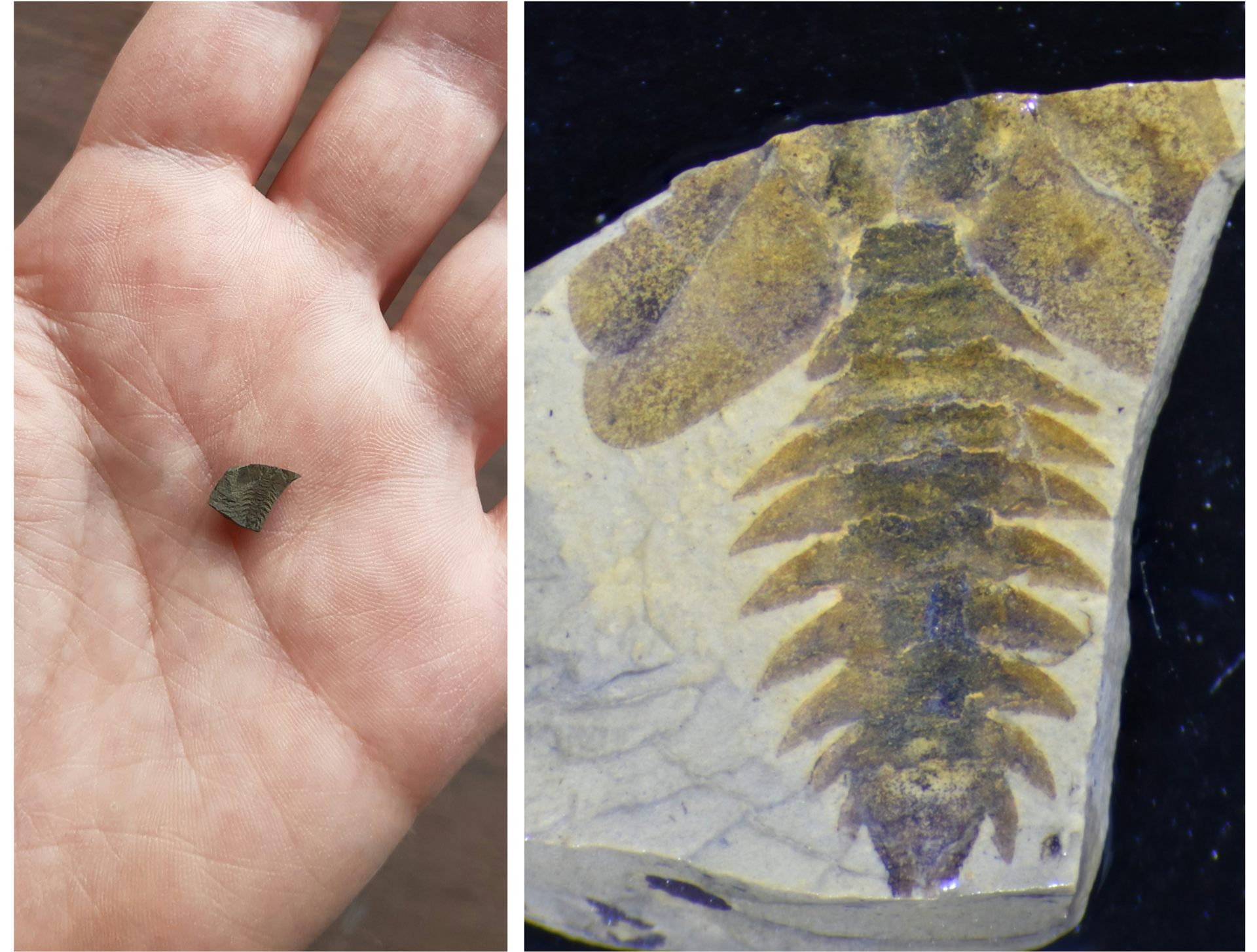

In a new paper, my colleagues and I provide the first glimpse of such an ecosystem. We have found a profusion of fossils of tiny insects that have never been found before, as well as important plant specimens that are changing our understanding of how they evolved.

Our findings give fresh insights into the effects of extinction events on ecosystems. The subject has taken on great urgency in the face of what scientists are calling the sixth great extinction event, which is being driven by the current trend of global warming.

For the past few years we have been excavating a small, nondescript rock outcrop near Sutherland in the Northern Cape.

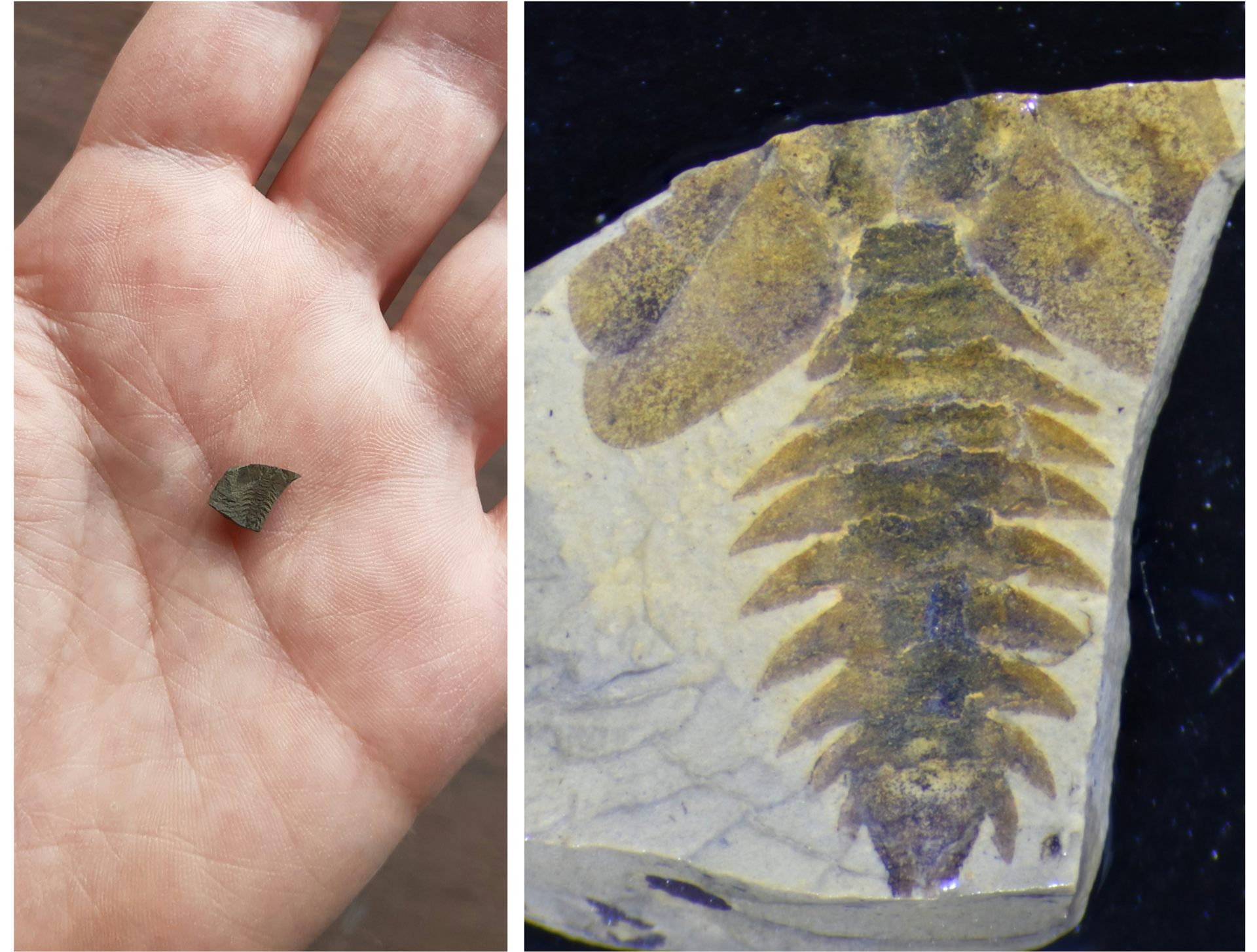

This outcrop is yielding untold fossil treasures of plants, insects and other invertebrates that are new to science. These unique fossils, some only a few millimetres long, are telling us about what lived in and around a calm pool on a delta plain during the middle Permian period between 266 million and 268 million years ago. Rocks of this age contain fossils of the oldest therapsids, a group of reptiles that eventually gave rise to the mammals.

Other life of this time included the lizard-like ancestors of tortoises, large amphibians that lurked like crocodiles just below the water surface, and forests dominated by a tree called Glossopteris with an understorey of spore-producing plants such as mosses, ferns and horsetails.

Teams of palaeontologists have discovered and excavated many hundreds of vertebrate fossils in the western and southern Karoo of South Africa that date back to the Permian, including the Sutherland District and surrounding areas. But the kinds of rocks that are rich in vertebrate fossil bones tend not to preserve plants and invertebrates. These seem to require the more anoxic, acidic conditions present in calm lakes and pools for high fidelity preservation, whereas bones preserve well in more oxygen-rich settings.

This makes it difficult to understand the ecosystems of this time – and means our discoveries are especially astonishing. These include the oldest freshwater leech, a record that pushes back the known range of this group by 40 million years, and the oldest water mites by 166 million years.

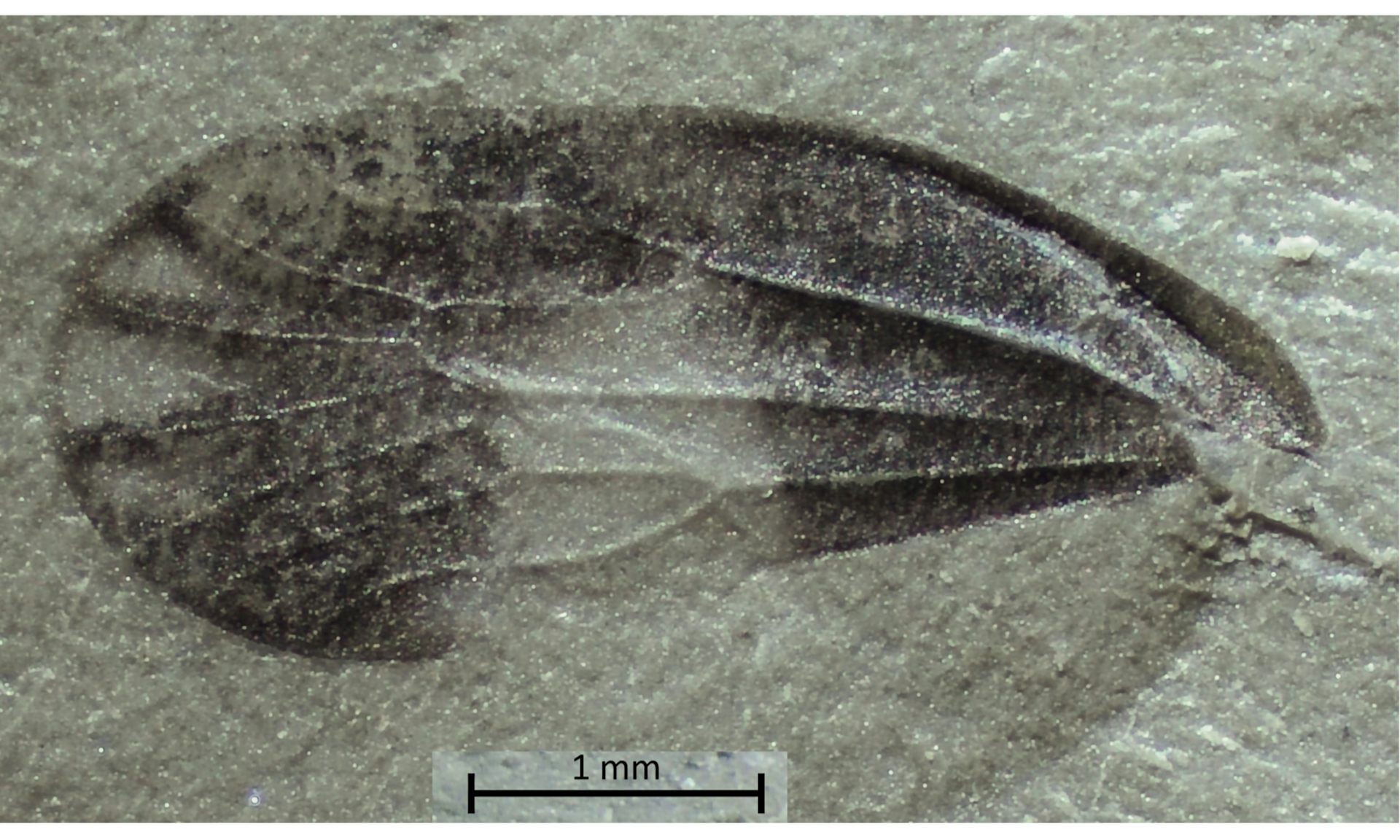

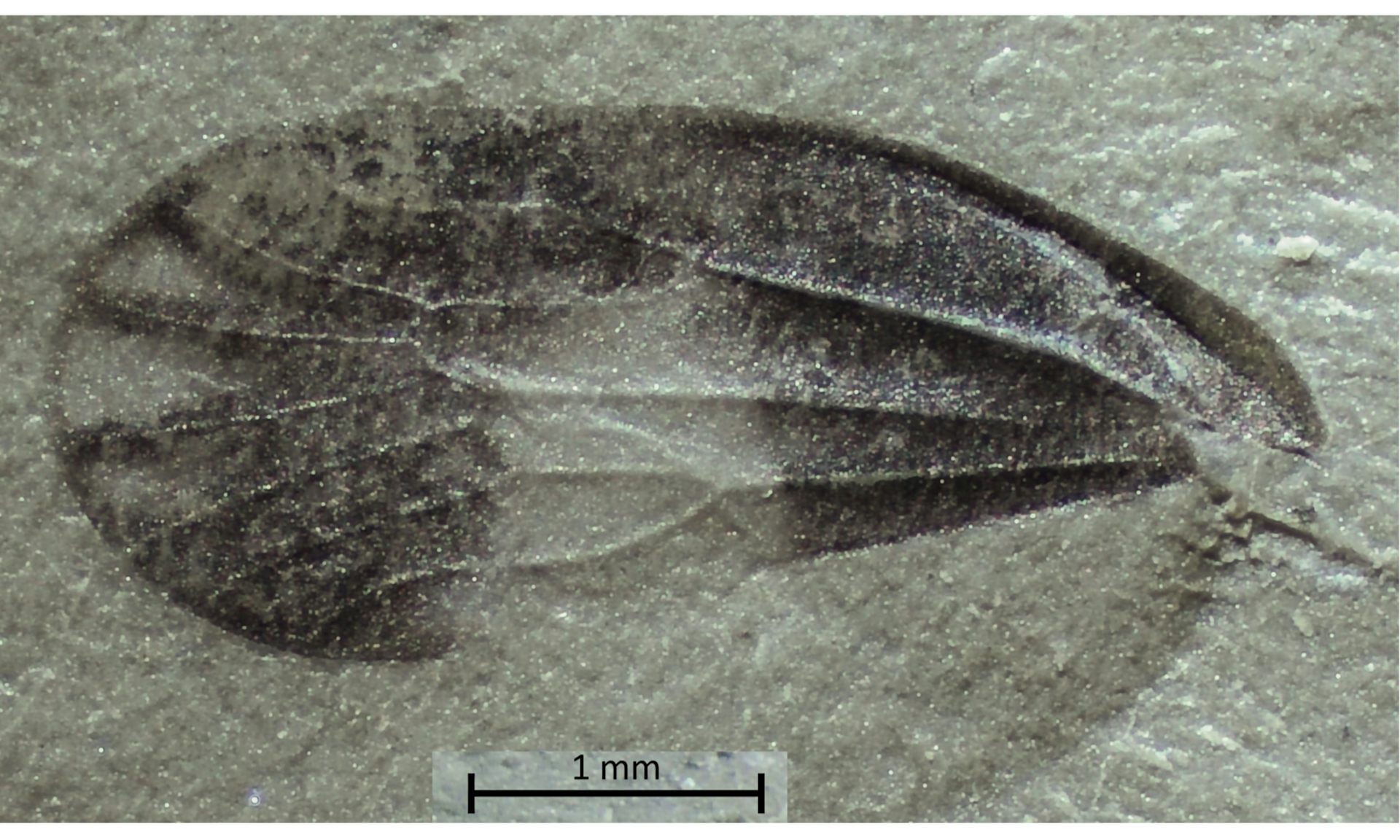

Other exciting finds include the oldest damsel-fly and oldest stoneflies from Gondwana, as well as a profusion of the tiny, aquatic, immature stages (nymphs) of an extinct group called the Palaeodictyoptera. Many of the insect wings we have found have yet to be identified.

There are also mosses and liverworts, tiny soft plants that were among the first to colonise land. They too, have a very poor fossil record, and we have found both at our site. The liverwort is the oldest in Africa and one of only a few records for the Permian period globally.

There are also mosses and liverworts, tiny soft plants that were among the first to colonise land. They too, have a very poor fossil record, and we have found both at our site. The liverwort is the oldest in Africa and one of only a few records for the Permian period globally.

One of the most exciting finds is the dense accumulations of the male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant, an unbelievably rare occurrence that is shedding light on the evolution and classification of this important coal-forming plant.

Great potential

Great potential

Our work has been slow. Excavations have involved a lot of sitting on spiky rocks in the sun for weeks on end, extracting tiny pieces of mudrock and then examining them with a magnifying hand lens.

The fossil site is still producing new weird and wonderful plants and invertebrates, and will keep us busy for a while. There is also great potential for finding other sites in the region. The thousands of plants and insects we have collected so far are being carefully curated and studied at the Albany Museum in Makhanda. We are keenly aware of the need to conserve this precious part of South Africa’s protected natural heritage.

Our work to better understand the organisms we’re finding provides knowledge about how and when they evolved and interacted as well as about local climate, how their distributions changed through time, how the positions of the continents changed, and the effects of deserts, mountain ranges and seas on the movement and evolution of life.

This is very important when trying to understand extinction events such as the Great Dying, which marked the end of the Permian 252 million years ago. It destroyed most life in the oceans and on land and – in a chilling echo of the current global climate crisis – was driven by hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activity that produced huge amounts of greenhouse gases, leading to an increase in global temperatures.

Rosemary Prevec, Palaeontologist, Rhodes University

Creationist frauds who want to convince their cult members that the Theory of Evolution is about to be replaced in mainstream science by their childish superstition, and so become the first scientific theory ever to be replaced with an evidence-free superstition involving imaginary supernatural entities, have to keep them ignorant of papers such as this one which has just been published in Communications Biology.

The paper, by a team of scientists led by Rosemary Prevec, a palaeontologist with Rhodes University Department of Botany, and the Department of Earth Science, Albany Museum, Makhanda, South Africa, reports on an exceptionally well preserved collection of fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids and plants - what is known to science as a 'Lagerstätte'. What's more, the formation has 'robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context', in other words, the fossils can be accurately placed in time and the changing geography of the time - some 266–268 million years ago in a river delta, when Earth had just two major landmass known as Gondwana and Laurasia, the northern and southern parts of Pangea respectively, before they were broken up and in some cases forced together by tectonic forces to form today’s major continents.

These fossils enabled the team to reconstruct the ecosystem of the time. An ecosystem is the result of interactions between species of animals and plants in a given area - the fundamental conditions for evolution to occur, as the ecosystem changes in response to internal and external pressures.

The team leader, Rosemary Prevec, has written the following article in The Conversation to explain the background to the discovery and its significance in terms of understanding the evolution of some species and the extinction of others. The Theory of Evolution is, of course, fundamental to research such as this in order to make sense of the observations. Note that nowhere does the author show the slightest doubt about the TOE's value in that understanding.

Her article is reproduced under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original can be read here.

Find out more about The Conversation, here.

Exquisite new fossils from South Africa offer a glimpse into a thriving ecosystem 266 million years ago

A fossilised insect wing with some of its colouration preserved is just one tiny treasure emerging from the site.

Rose Prevec

Rosemary Prevec, Rhodes University

South Africa is famous for its amazingly rich and diverse fossil record. The country’s rocks document more than 3.5 billion years of life on Earth: ancient forms of bacterial life, the emergence of life onto land, the evolution of seed-producing plants, reptiles, dinosaurs and mammals – and humanity.

Many will be familiar with hominid fossils such as the Australopithecus africanus skull Mrs (or is it Mr?) Ples and the paradigm-shifting Taung child. Less well known and equally important fossils such as the oldest terrestrial vertebrates in the ancient supercontinent Gondwana, which document the first steps from the ocean and onto land, have also emerged from South Africa. The country’s wealth of fossils is due in part to the region’s unique geology, which documents 100 million years of nearly continuous deposition in its Karoo Basin.

Fossils also hold clues to climatic shifts, from the great Carboniferous ice age over 300 million years ago, to the huge dunes of blazing Jurassic deserts where dinosaurs roamed 200 million years ago. Scientists can read the devastation of the mass extinction events that destroyed global ecosystems and changed the course of Earth’s history.

But in the race to understand the “big picture” of the evolution of life and to distil its dramatic ups and downs into punchy headlines, it is easy to forget the small and quiet things. Pause, and consider what life looked like on an average day, in a world without humans, mammals, birds, butterflies, flowers, or even dinosaurs. What was it like on the shores of a rippling lake, on a drowsy summer afternoon, 266 million years ago in what’s now the Northern Cape province of South Africa?

The search, and what we found

In a new paper, my colleagues and I provide the first glimpse of such an ecosystem. We have found a profusion of fossils of tiny insects that have never been found before, as well as important plant specimens that are changing our understanding of how they evolved.

Our findings give fresh insights into the effects of extinction events on ecosystems. The subject has taken on great urgency in the face of what scientists are calling the sixth great extinction event, which is being driven by the current trend of global warming.

For the past few years we have been excavating a small, nondescript rock outcrop near Sutherland in the Northern Cape.

This outcrop is yielding untold fossil treasures of plants, insects and other invertebrates that are new to science. These unique fossils, some only a few millimetres long, are telling us about what lived in and around a calm pool on a delta plain during the middle Permian period between 266 million and 268 million years ago. Rocks of this age contain fossils of the oldest therapsids, a group of reptiles that eventually gave rise to the mammals.

Other life of this time included the lizard-like ancestors of tortoises, large amphibians that lurked like crocodiles just below the water surface, and forests dominated by a tree called Glossopteris with an understorey of spore-producing plants such as mosses, ferns and horsetails.

Teams of palaeontologists have discovered and excavated many hundreds of vertebrate fossils in the western and southern Karoo of South Africa that date back to the Permian, including the Sutherland District and surrounding areas. But the kinds of rocks that are rich in vertebrate fossil bones tend not to preserve plants and invertebrates. These seem to require the more anoxic, acidic conditions present in calm lakes and pools for high fidelity preservation, whereas bones preserve well in more oxygen-rich settings.

This makes it difficult to understand the ecosystems of this time – and means our discoveries are especially astonishing. These include the oldest freshwater leech, a record that pushes back the known range of this group by 40 million years, and the oldest water mites by 166 million years.

Other exciting finds include the oldest damsel-fly and oldest stoneflies from Gondwana, as well as a profusion of the tiny, aquatic, immature stages (nymphs) of an extinct group called the Palaeodictyoptera. Many of the insect wings we have found have yet to be identified.

A fossil of an insect nymph - so tiny that it is dwarfed by a human hand - and, on the right, seen under a microscope.

Credit: Rose Prevec

One of the most exciting finds is the dense accumulations of the male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant, an unbelievably rare occurrence that is shedding light on the evolution and classification of this important coal-forming plant.

Male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant.

Credit: Rose Prevec

Our work has been slow. Excavations have involved a lot of sitting on spiky rocks in the sun for weeks on end, extracting tiny pieces of mudrock and then examining them with a magnifying hand lens.

The fossil site is still producing new weird and wonderful plants and invertebrates, and will keep us busy for a while. There is also great potential for finding other sites in the region. The thousands of plants and insects we have collected so far are being carefully curated and studied at the Albany Museum in Makhanda. We are keenly aware of the need to conserve this precious part of South Africa’s protected natural heritage.

Our work to better understand the organisms we’re finding provides knowledge about how and when they evolved and interacted as well as about local climate, how their distributions changed through time, how the positions of the continents changed, and the effects of deserts, mountain ranges and seas on the movement and evolution of life.

This is very important when trying to understand extinction events such as the Great Dying, which marked the end of the Permian 252 million years ago. It destroyed most life in the oceans and on land and – in a chilling echo of the current global climate crisis – was driven by hundreds of thousands of years of volcanic activity that produced huge amounts of greenhouse gases, leading to an increase in global temperatures.

Rosemary Prevec, Palaeontologist, Rhodes University

Fig. 4: Key plant fossil discoveries from the Onder Karoo locality.

a Glossopteris leaf with abundant platyspermic seeds to the left. Arrow indicates adjacent Lidgettonia sp. 1 fructification, the likely source of the seeds. b Lidgettonia sp. 1: large scale leaf with at least five pairs of cupules attached. c Slab showing mixed mat of male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant. d New dictyopteridean, seed-bearing glossopterid fructification Ottokaria. e Female cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Lidgettonia sp. 2 fertiligers attached to a shoot. f Male cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Eretmonia sp. polleniferous scales attached to a shoot. g Glossopteris leaves, arrows indicate sites of margin-feeding by insects. h Glossopteris leaf with arrows indicating large excisions caused by insect feeding, note pronounced staining of plant reaction tissue. i Probable moss sporophytes, arrows indicate moss capsules. j Thallose liverwort with dichotomous branching, notched termini, hydroids, typical epidermal patterning (ep, arrow) and possible gemma cups (gc, arrows).

a Glossopteris leaf with abundant platyspermic seeds to the left. Arrow indicates adjacent Lidgettonia sp. 1 fructification, the likely source of the seeds. b Lidgettonia sp. 1: large scale leaf with at least five pairs of cupules attached. c Slab showing mixed mat of male and female cones of the Glossopteris plant. d New dictyopteridean, seed-bearing glossopterid fructification Ottokaria. e Female cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Lidgettonia sp. 2 fertiligers attached to a shoot. f Male cone of Glossopteris plant: multiple Eretmonia sp. polleniferous scales attached to a shoot. g Glossopteris leaves, arrows indicate sites of margin-feeding by insects. h Glossopteris leaf with arrows indicating large excisions caused by insect feeding, note pronounced staining of plant reaction tissue. i Probable moss sporophytes, arrows indicate moss capsules. j Thallose liverwort with dichotomous branching, notched termini, hydroids, typical epidermal patterning (ep, arrow) and possible gemma cups (gc, arrows).

Fig. 5: A selection of newly discovered invertebrate fossils from the Onder Karoo locality.

a AM14859: exuviae of a nymph (Palaeodictyopterida). b AM13265: stonefly nymph (Plecoptera). c AM11348: cluster of plecopteran nymph exuviae associated with glossopterid seeds. d AM11296: distal fragment of a wing of Afrozygopteron inexpectatus45, a Protozygoptera (an early damselfly-like Odonatoptera), with sclerotized costo-apical pterostigma (arrow). e AM11389: forewing of an ‘ice crawler’, Colubrosopterum karooensis (a new genus of ‘Grylloblattodea’, Liomopteridae46). f AM14864d: two forewings of Protelytoptera. g AM14864e: two forewings of Anthracoptilidae (Paoliida). h AM14858ab: composite image of part and counterpart of a hemipteran forewing (Prosbolidae). i AM11298a: hemipteran forewing with pattern of wing colouration preserved (Scytinopteridae). j AM11157a: large forewing of a cicadamorph with pattern of colouration preserved (Hemiptera, Pereboriidae). k terrestrial nymph/nymph exuviae (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). l annelid worm, probable Clitellata (leech) with circular sucker (arrow). m AM11282b: elytron of a beetle with punctate ornamentation (Coleoptera, Permocupedidae). n AM14856: water mite (Acari, Hydrachnidia).

a AM14859: exuviae of a nymph (Palaeodictyopterida). b AM13265: stonefly nymph (Plecoptera). c AM11348: cluster of plecopteran nymph exuviae associated with glossopterid seeds. d AM11296: distal fragment of a wing of Afrozygopteron inexpectatus45, a Protozygoptera (an early damselfly-like Odonatoptera), with sclerotized costo-apical pterostigma (arrow). e AM11389: forewing of an ‘ice crawler’, Colubrosopterum karooensis (a new genus of ‘Grylloblattodea’, Liomopteridae46). f AM14864d: two forewings of Protelytoptera. g AM14864e: two forewings of Anthracoptilidae (Paoliida). h AM14858ab: composite image of part and counterpart of a hemipteran forewing (Prosbolidae). i AM11298a: hemipteran forewing with pattern of wing colouration preserved (Scytinopteridae). j AM11157a: large forewing of a cicadamorph with pattern of colouration preserved (Hemiptera, Pereboriidae). k terrestrial nymph/nymph exuviae (Hemiptera, Sternorrhyncha). l annelid worm, probable Clitellata (leech) with circular sucker (arrow). m AM11282b: elytron of a beetle with punctate ornamentation (Coleoptera, Permocupedidae). n AM14856: water mite (Acari, Hydrachnidia).

More detail is given in the abstract to the team's open access paper in Communications Biology:

AbstractAnd another research paper casually refutes the Creationist lie that the TOE is being increasingly rejected by serious scientists.

Continental ecosystems of the middle Permian Period (273–259 million years ago) are poorly understood. In South Africa, the vertebrate fossil record is well documented for this time interval, but the plants and insects are virtually unknown, and are rare globally. This scarcity of data has hampered studies of the evolution and diversification of life, and has precluded detailed reconstructions and analyses of ecosystems of this critical period in Earth’s history. Here we introduce a new locality in the southern Karoo Basin that is producing exceptionally well-preserved and abundant fossils of novel freshwater and terrestrial insects, arachnids, and plants. Within a robust regional geochronological, geological and biostratigraphic context, this Konservat- and Konzentrat-Lagerstätte offers a unique opportunity for the study and reconstruction of a southern Gondwanan deltaic ecosystem that thrived 266–268 million years ago, and will serve as a high-resolution ecological baseline towards a better understanding of Permian extinction events.

Prevec, R., Nel, A., Day, M.O. et al.

South African Lagerstätte reveals middle Permian Gondwanan lakeshore ecosystem in exquisite detail.

Commun Biol 5, 1154 (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-022-04132-y

Copyright: © 2022 The authors.

Published by Springer Nature Ltd. Open access

Reprinted under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

Labels:

Biology

,

Creationism in Crisis

,

Ecology

,

Evolution

,

Palaeontology

,

Science

Tuesday 20 September 2022

Environment News - How Many Ants Are There?

Earth harbours 20,000,000,000,000,000 ants – and they weigh more than wild birds and mammals combined

Many years ago, when I was a medical research technician for Oxford University, the lab I worked in suddenly had a problem with tiny yellow ants that were all over the place, so we called in a university entomologist. He identified them as pharaoh ants, a recently introduced species to the UK that was thriving in centrally-heated buildings.

We weren’t the only department with the problem because, as he explained, there was a large colony of possibly a billion individual ants somewhere in underground heating system that piped heating from a central boiler room serving many different buildings behind the Natural History and Pitt Rivers Museums, but they were harmless anyway, although it wasn't pleasant to find they'd discovered your pack of sandwiches and had laid a trail to it along which thousands were now streaming in a thin yellow line, carrying your lunch away, crumb by crumb. They especially liked ham, but wouldn't turn down cheese or egg.

We used to have a bit of fun with them, being research biologists. We would place a strip of paper across their trail and wait until they had found their way across it to pick up their trail on the other side and laid a new connecting scent trail on the paper, then we would move the paper several inches sideways and watch as they explored the paper to discover the trail across it now several inches away, cross it and then explore to find the old trail. Then we would remove the paper and watch as they still followed along where the edges of the paper strip had been to where the trail used to cross the paper strip, lay a new trail and follow back along what had been the edge of the paper to pick up their old trail. Sometimes an enterprising scout would find a shortcut and establish a new trail. In this way, we could create a complicated zig-zag trail and make them work for their free lunch! It would take them several hours to re-establish a shorter trail.

Incidentally, this also proved they were laying a trail of some sort. The trail could also be washed away with an alcohol swab, showing it was almost certainly a chemical of some sort.

But enough about the fun we had with our resident pharaoh ants.

Our billion-strong colony was a mere speck in the ocean, according to research by an Australian team. They have conservatively estimated that there are about 20 quadrillion ants alive on Earth at any one time - that's 20 followed by 15 zeros. Each of those ants will have about 250,000 brain cells alone and probably ten times as many other cells in their body. Each cell will contain hundreds, maybe thousands of proteins, each of which will need to be folded precisely to function correctly.

One of the tricks Creationists frauds fool their dupes with is to calculate how many different ways a protein can be folded then pretend to have estimated the chance of it being folded in exactly the right way to be vanishingly small, then hit their credulous audience with a false dichotomy fallacy and claim this proves the locally popular god must have arranged it.

Really? for every one of those sextillions of proteins in every one of those cells in all 20 quadrillion ants? And then there are the countless trillions of cells in other species! No wonder it doesn't have time to prevent children dying of malaria, AIDS or starvation in Africa!

You see, we can all play the big scary number tactic! But isn't it much more likely that the way proteins are folded is a function of the way they are manufactured by a cell, using nothing more complicated than the laws of chemistry and physics, than that it was all done by which ever deity the frauds are pushing, the existence of which and its modus operandum have never been demonstrated or witnessed?

So, leaving that major problem for Creations aside, how was the number, 20 quadrillion, arrived at for the Earthly population of ants, which incidentally means their combined weight of dry carbon is about 12 million tonnes, which exceeds that of all birds and mammals combined! The authors explain their methodology in an open access article in The Conversation, reprinted below under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original article can be read here.

Mark Wong, The University of Western Australia; Benoit Guénard, University of Hong Kong; François Brassard, Charles Darwin University; Patrick Schultheiss, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg; Runxi Wang, University of Hong Kong, and Sabine Nooten, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg

Mark Wong, The University of Western Australia; Benoit Guénard, University of Hong Kong; François Brassard, Charles Darwin University; Patrick Schultheiss, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg; Runxi Wang, University of Hong Kong, and Sabine Nooten, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg

Have you ever wondered exactly how many ants live on Earth? Possibly not, but it’s certainly a question we’ve asked ourselves.

Our research published today provides an approximate answer. We conservatively estimate our planet harbours about 20 quadrillion ants. That’s 20 thousand million millions, or in numerical form, 20,000,000,000,000,000 (20 with 15 zeroes).

We further estimate the world’s ants collectively constitute about 12 million tonnes of dry carbon. This exceeds the mass of all the world’s wild birds and wild mammals combined. It’s also equal to about one-fifth of the total weight of humans.

Eminent biologist Edward O. Wilson once said insects and other invertebrates are “the little things that run the world” – and he was right. Ants, in particular, are a crucial part of nature. Among other roles, ants aerate the soil, disperse seeds, break down organic material, create habitat for other animals and form an important part of the food chain.

Estimating ant numbers and mass provides an important baseline from which to monitor ant populations amid worrying environmental changes.

Counting the world’s ants

There are more than 15,700 named species and subspecies of ants, and many others not yet named by science. Ants’ high degree of social organisation has enabled them to colonise nearly all ecosystems and regions around the globe.

The astounding ubiquity of ants has prompted many naturalists to contemplate their exact number on Earth. But these were basically educated guesses. Systematic, evidence-based estimates have been lacking.

Our research involved an analysis of 489 studies of ant populations conducted by fellow ant scientists from around the world. This included non-English literature, in languages such as Spanish, French, German, Russian, Mandarin and Portuguese.

The research spanned all continents and major habitats including forests, deserts, grasslands and cities. They used standardised methods for collecting and counting ants such as pitfall traps and leaf litter samples. As you can imagine, this is often tedious work.

From all this, we estimate there are approximately 20 quadrillion ants on Earth. This figure, though conservative, is between two and 20 times higher than previous estimates.

The previous figures employed a “top-down” approach by assuming ants comprise about 1% of the world’s estimated insect population. In contrast, our “bottom-up” estimate is more reliable because it uses data on ants observed directly in the field and makes fewer assumptions.

Our next step was to work out how much all these ants weigh. The mass of organisms is typically measured in terms of their carbon makeup. We estimated that 20 quadrillion average-sized ants corresponds to a dry weight or “biomass” of approximately 12 million tonnes of carbon.

This is more than the combined biomass of wild birds and mammals – and about 20% of total human biomass.

Carbon makes up about half the dry weight of an ant. If the weight of other bodily elements was included, the total mass of the world’s ants would be higher still.

We also found ants are distributed unevenly on Earth’s surface. They vary sixfold between habitats and generally peak in the tropics. This underscores the importance of tropical regions in maintaining healthy ant populations.

Ants were also particularly abundant in forests, and surprisingly, in arid regions. But they become less common in human-made habitats.

Our findings come with a few caveats. For example, the sampling locations in our dataset are unevenly distributed across geographic regions. And the vast majority of samples were collected from the ground layer, meaning we have very little information about ant numbers in trees or underground. This means our findings are somewhat incomplete.

We all need ants

Ants also provide vital “ecosystem services” for humans. For instance, a recent study found ants can be more effective than pesticides at helping farmers produce food.

Ants have also developed tight interactions with other organisms – and some species cannot survive without them.

For example, some birds rely on ants to flush out their prey. And thousands of plant species either feed or house ants in exchange for protection, or dispersal of their seeds. And many ants are predators, helping to keep populations of other insects in check.

Alarmingly, global insect numbers are declining due to threats such as habitat destruction and fragmentation, chemical use, invasive species and climate change.

But data on insect biodiversity is alarmingly scarce. We hope our study provides a baseline for further research to help fill this gap.

It’s in humanity’s interest to monitor ant populations. Counting ants is not difficult, and citizen scientists from all over the world could help investigate how these important animals are faring at a time of great environmental change. Mark Wong, Forrest Fellow, The University of Western Australia;

Mark Wong, Forrest Fellow, The University of Western Australia;

Benoit Guénard, Associate professor, University of Hong Kong;

François Brassard, PhD candidate, Charles Darwin University;

Patrick Schultheiss, Temporary Principal Investigator, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg;

Runxi Wang, PhD candidate, University of Hong Kong,

and Sabine Nooten, Temporary Principal Investigator, Julius Maximilian University of Würzburg

The team have published their findings in the journal PNAS. Although the main body of thr paper is behind a paywall, the abstract is pubished open access:

And yet these are harmless unless you annoy them then they can give a mild sting, more like a pinprick, really. They are incredibly useful in gardens where they account for thousands of caterpillars. Please treat them with respect. If they do come into your house, look upon them as cleaners because they'll be finding food crumbs and spilt sugar, etc. Keeping the floor and surfaces clean, and keeping food covered in sealed containers, will mean you won't get visits.

We need our ants - all 20 quadrillion of them!

Many years ago, when I was a medical research technician for Oxford University, the lab I worked in suddenly had a problem with tiny yellow ants that were all over the place, so we called in a university entomologist. He identified them as pharaoh ants, a recently introduced species to the UK that was thriving in centrally-heated buildings.

We weren’t the only department with the problem because, as he explained, there was a large colony of possibly a billion individual ants somewhere in underground heating system that piped heating from a central boiler room serving many different buildings behind the Natural History and Pitt Rivers Museums, but they were harmless anyway, although it wasn't pleasant to find they'd discovered your pack of sandwiches and had laid a trail to it along which thousands were now streaming in a thin yellow line, carrying your lunch away, crumb by crumb. They especially liked ham, but wouldn't turn down cheese or egg.

We used to have a bit of fun with them, being research biologists. We would place a strip of paper across their trail and wait until they had found their way across it to pick up their trail on the other side and laid a new connecting scent trail on the paper, then we would move the paper several inches sideways and watch as they explored the paper to discover the trail across it now several inches away, cross it and then explore to find the old trail. Then we would remove the paper and watch as they still followed along where the edges of the paper strip had been to where the trail used to cross the paper strip, lay a new trail and follow back along what had been the edge of the paper to pick up their old trail. Sometimes an enterprising scout would find a shortcut and establish a new trail. In this way, we could create a complicated zig-zag trail and make them work for their free lunch! It would take them several hours to re-establish a shorter trail.

Incidentally, this also proved they were laying a trail of some sort. The trail could also be washed away with an alcohol swab, showing it was almost certainly a chemical of some sort.

But enough about the fun we had with our resident pharaoh ants.

Our billion-strong colony was a mere speck in the ocean, according to research by an Australian team. They have conservatively estimated that there are about 20 quadrillion ants alive on Earth at any one time - that's 20 followed by 15 zeros. Each of those ants will have about 250,000 brain cells alone and probably ten times as many other cells in their body. Each cell will contain hundreds, maybe thousands of proteins, each of which will need to be folded precisely to function correctly.

One of the tricks Creationists frauds fool their dupes with is to calculate how many different ways a protein can be folded then pretend to have estimated the chance of it being folded in exactly the right way to be vanishingly small, then hit their credulous audience with a false dichotomy fallacy and claim this proves the locally popular god must have arranged it.

Really? for every one of those sextillions of proteins in every one of those cells in all 20 quadrillion ants? And then there are the countless trillions of cells in other species! No wonder it doesn't have time to prevent children dying of malaria, AIDS or starvation in Africa!

You see, we can all play the big scary number tactic! But isn't it much more likely that the way proteins are folded is a function of the way they are manufactured by a cell, using nothing more complicated than the laws of chemistry and physics, than that it was all done by which ever deity the frauds are pushing, the existence of which and its modus operandum have never been demonstrated or witnessed?

So, leaving that major problem for Creations aside, how was the number, 20 quadrillion, arrived at for the Earthly population of ants, which incidentally means their combined weight of dry carbon is about 12 million tonnes, which exceeds that of all birds and mammals combined! The authors explain their methodology in an open access article in The Conversation, reprinted below under a Creative Commons license, reformatted for stylistic consistency. The original article can be read here.

Earth harbours 20,000,000,000,000,000 ants – and they weigh more than wild birds and mammals combined

Shutterstock

Have you ever wondered exactly how many ants live on Earth? Possibly not, but it’s certainly a question we’ve asked ourselves.

Our research published today provides an approximate answer. We conservatively estimate our planet harbours about 20 quadrillion ants. That’s 20 thousand million millions, or in numerical form, 20,000,000,000,000,000 (20 with 15 zeroes).

We further estimate the world’s ants collectively constitute about 12 million tonnes of dry carbon. This exceeds the mass of all the world’s wild birds and wild mammals combined. It’s also equal to about one-fifth of the total weight of humans.

Eminent biologist Edward O. Wilson once said insects and other invertebrates are “the little things that run the world” – and he was right. Ants, in particular, are a crucial part of nature. Among other roles, ants aerate the soil, disperse seeds, break down organic material, create habitat for other animals and form an important part of the food chain.

Estimating ant numbers and mass provides an important baseline from which to monitor ant populations amid worrying environmental changes.

Many ant species are important seed dispersers. Here, two worker Meranoplus ants carry a seed back to their nest.

Credit: Francois Brassard

Counting the world’s ants

There are more than 15,700 named species and subspecies of ants, and many others not yet named by science. Ants’ high degree of social organisation has enabled them to colonise nearly all ecosystems and regions around the globe.

The astounding ubiquity of ants has prompted many naturalists to contemplate their exact number on Earth. But these were basically educated guesses. Systematic, evidence-based estimates have been lacking.

Our research involved an analysis of 489 studies of ant populations conducted by fellow ant scientists from around the world. This included non-English literature, in languages such as Spanish, French, German, Russian, Mandarin and Portuguese.

The research spanned all continents and major habitats including forests, deserts, grasslands and cities. They used standardised methods for collecting and counting ants such as pitfall traps and leaf litter samples. As you can imagine, this is often tedious work.

A researcher installs a pitfall trap, a standard method for collecting ants that crawl across the ground surface.

Credit: Francois Brassard

From all this, we estimate there are approximately 20 quadrillion ants on Earth. This figure, though conservative, is between two and 20 times higher than previous estimates.

The previous figures employed a “top-down” approach by assuming ants comprise about 1% of the world’s estimated insect population. In contrast, our “bottom-up” estimate is more reliable because it uses data on ants observed directly in the field and makes fewer assumptions.

Our next step was to work out how much all these ants weigh. The mass of organisms is typically measured in terms of their carbon makeup. We estimated that 20 quadrillion average-sized ants corresponds to a dry weight or “biomass” of approximately 12 million tonnes of carbon.

This is more than the combined biomass of wild birds and mammals – and about 20% of total human biomass.

Carbon makes up about half the dry weight of an ant. If the weight of other bodily elements was included, the total mass of the world’s ants would be higher still.

We also found ants are distributed unevenly on Earth’s surface. They vary sixfold between habitats and generally peak in the tropics. This underscores the importance of tropical regions in maintaining healthy ant populations.

Ants were also particularly abundant in forests, and surprisingly, in arid regions. But they become less common in human-made habitats.